How to Approach Oxford’s Language Tests in 2025: The MLAT, LAT & OLAT

In this blog, one of U2’s 1st Class Oxford Linguistics and Spanish graduates, leads you through the key components of Oxford’s language tests: The MLAT, LAT and OLAT, including when to begin studying, what the tests look like, how to prepare and key strategies on the day. Find out how to crack the language-based puzzles and demonstrate your creativity and flexible thinking!

What is the MLAT? What Tests Do I Have To Sit?

The MLAT is somewhat different to other tests set by Oxford, in that it has a large number of permutations - and it is up to you to know which sections of the tests you have to sit. It is also worth saying straight off the bat that, if you are applying for one of Oxford’s many joint courses, you will need to sit both tests. For example, a student applying for English and French will have to sit both the ELAT and the French portion of the MLAT. History and beginner’s Russian? You’ll need to sit both the HAT and the Aptitude Test section of the MLAT (more info below).

Oxford has created a useful and comprehensive guide to the combinations that are required, which I strongly recommend that you check for yourself. But the bare bones are:

If you are already studying the target language in school (e.g. you are sitting A-Level Italian), you will need to sit the portion of the MLAT specific to that language.

If you are applying for a beginner’s language, or Russian at any level, you will need to sit the Language Aptitude Test (sometimes called the LAT), which is one section inside the MLAT.

If you are applying for a Joint Course (e.g. a language with English, History, or Classics), you will need to sit that subject’s test as well (e.g. ELAT, HAT, CAT, etc.)

The exception is Linguistics; applicants for Linguistics no longer need to sit a test for this portion of their degree. The Linguistics section was discontinued after 2019. I think this is a shame, because it was actually rather fun!

Candidates for one of the following Middle Eastern languages - Hebrew, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, or Jewish Studies - will also sit the Oriental Languages Aptitude Test. This is identical to the LAT, so please read that section below for more information.

Students for Philosophy and a Modern Language must also sit the Philosophy section of the MLAT, a one-hour long test that appears in the same booklet as the rest of the MLAT. Unfortunately I’m no philosopher, so discussion of that section is outside the scope of this guide. Book a free consultation with U2 who will be able to refer mentors who can offer guidance on the Philosophy Test.

This all means that you will need to sit a maximum of two sections from the MLAT (some candidates will sit only one section), as well as whatever is required by the other half of your joint course, if applicable.

The good news, though, is that the tests inside the MLAT are fairly short, certainly compared with many other admissions tests at Oxford. All language tests (and the LAT) last just 30 minutes, and the Philosophy essay lasts an hour. The tests are also fairly predictable in their structure.

When to Begin Studying

I believe there is such a thing as beginning too early for the MLAT. That might sound counterintuitive, but hear me out: the test is fairly short, and it will be based on where Oxford expects your grammar and translation skills to be in the autumn term of your application year. If you are sitting a practice test about eight months earlier, you still have quite a bit of school studying to undertake before the test. Any scores or results from, say, February will therefore be unrepresentative.

For this reason, I recommend turning to the MLAT itself from roughly the summer holidays onwards. As with learning a language itself, little-and-often is usually the best strategy.

That’s not to say that you can’t make your life easier in the meantime, though! The MLAT is primarily an exercise in grammar and translation - so keep good, organised notes on the grammar you acquire, as well as keeping track of whatever idiosyncrasies of the language that you happen to notice (is there a particular pattern for formal writing, for example? Note it down, and save it for later).

The remainder of this guide is split into two parts - one for the language tests, and one for the LAT/OLAT.

Language Tests: Czech, French, German, Modern Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish

WHAT THE TEST LOOKS LIKE

No matter which language you wish to study, the tests all have fairly standard components: translation into the language, translation from the language into English, and a multiple-choice / gap-filling exercise based on grammatical knowledge. The allocation of marks varies according to the language (some place equal emphasis on all aspects; some emphasise translation), and this is something you should check when preparing. You are expected to answer all questions in the section. Each paper offers either 50 or 100 marks, depending on the year.

WHAT ARE THEY LIKELY TO ASK?

It is probable that you already have an intuitive knowledge of the sort of things that are the difficult grammar points of your chosen language. What grammar do you spend most time on in A-Level classes, for instance? The questions will likely target those same points. The language with which I am most familiar is Spanish. Students of Spanish are all too aware of the things that are fairly tricky when it comes to grammar! Some examples for Spanish are: use of the 4 past tenses and of the subjunctive, object pronouns, the passive, and verbs which work like gustar, for instance. This will, of course, depend on the language. German, say, has a much more rigid word order when compared to the supple syntax of Spanish - so this should form part of your revision too.

You might find it useful to look at, if it exists, the AS-Level syllabus for your chosen language. The MLAT predates the switch to linear A-Levels, so knowing what was expected at AS Level may be a good rule-of-thumb. However, I encourage you to look beyond that - to the complete specifications of your A-Level.

This may all feel daunting - but it shouldn’t. Yes, the paper is designed to stretch you, and it will be looking for good knowledge of some of the language’s quirks (such as irregular verbs, or knowledge that the word for people is always singular in Spanish “la gente”, but always plural in German “die Leute”). But trust me: you are already more familiar with these than you might think.

Most students, though, find the translations to be the most difficult - especially translations from English into the language. Again, there are things from your background knowledge of the language that should be applied. Many European languages have different forms of the word “you”, for instance: tú/usted in Spanish, du/Sie in German, ты/вы in Russian. You will need to decide which is best to use, according to the rest of the sentence. This is one small example, but there are of course many more - you are most likely familiar with some of them. As with any translation project, your aim is to write natural and appropriate sentences in the target language - so keep an eye out for these.

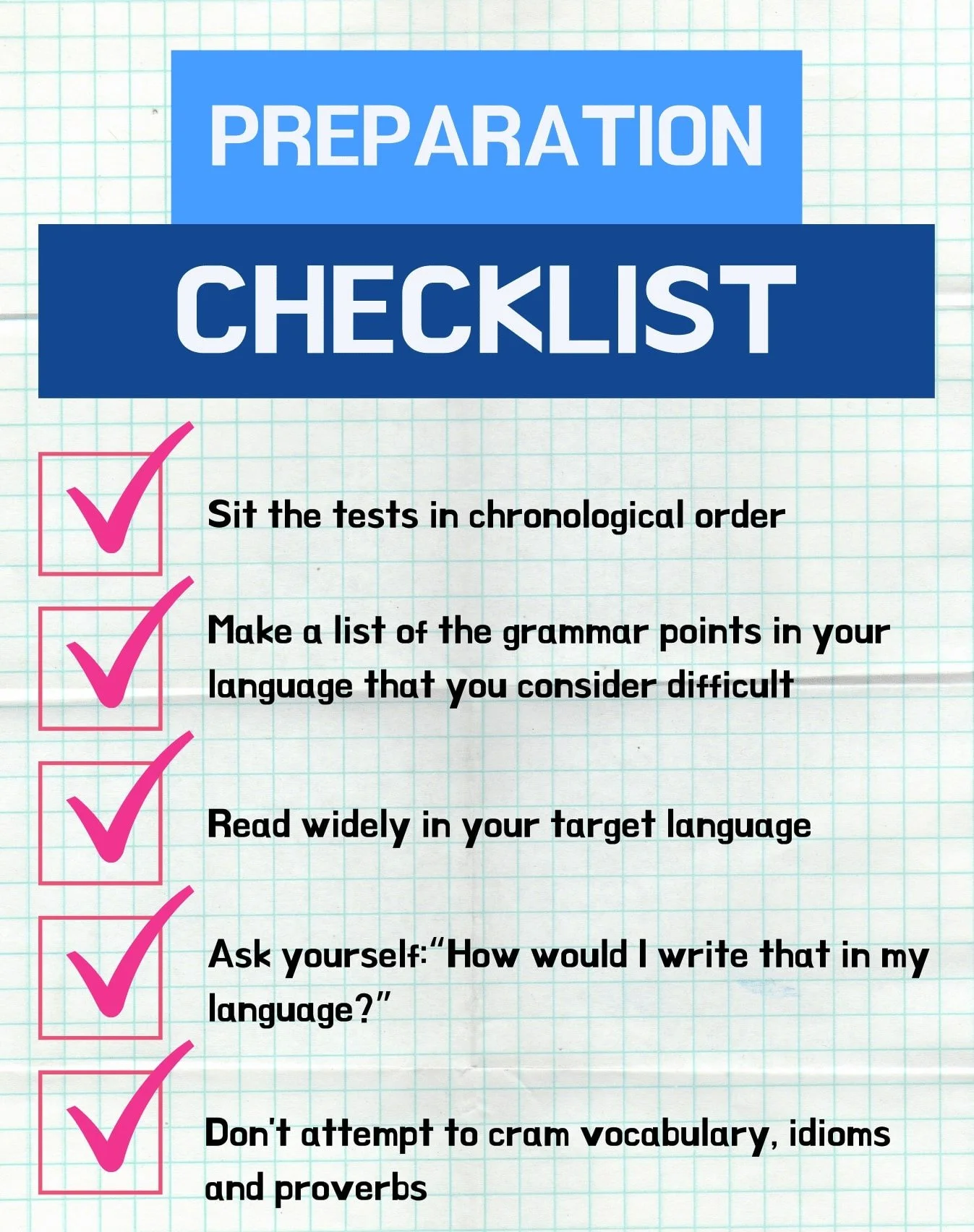

PREPARATION CHECKLIST

A good place to begin is past papers, which are freely available online. For language tests, I recommend sitting them in chronological order. This is not because they are getting more difficult year-on-year, but because the structure has changed slightly over time. The more recent the test, the more likely that the paper will look like the one you encounter on the day.

Make a list of the grammar points in your language that you consider difficult. This may be word order, a case system, irregulars, a gender system, verbs, or something else. Think of it as “the usual suspects” in your language. It is likely that the test will be probing you on this fine-grained detail - so organisation is key.

As translations often cover a series of registers - from informal to even a bit journalistic - I recommend reading widely in your target language. You do not need to take this on as an extra burden; in fact, since you should be reading widely in the language anyway (for personal statement texts, for background knowledge, and frankly for pure pleasure), this is something you are likely already doing. Think of it as killing two birds with one stone (or, in Polish, roasting two pieces of meat on one fire)! If you see an interesting structure, an unfamiliar word order, or any other interesting grammatical feature, try and track it down and investigate why. As mentioned before, note it down.

Practise translation in your head (or indeed on the page). “How would I write that in my language?”, ask yourself. Translation is not a piece of knowledge or a talent; it is a skill, and all skills are acquired through practice. Any piece of writing, in English or in your target language, is a potential translation - so give it a shot.

Something I do not recommend is a crazed attempt to cram as much vocabulary into your head as possible. These are language tests, not vocabulary tests! It is relatively unlikely that you will just happen to learn and recall the perfect word, so save your energy and work on other aspects of the test instead.

This includes idioms and proverbs. Some of the tests do occasionally include a saying or a phrase for translation (in both directions) but, again, it’s a fool’s errand to try and second-guess the test in this way. There are alternative strategies - see below.

STRATEGY ON THE DAY:

Start by checking the weighting of marks per section. If 20 out of the 100 marks are for the gap-fill exercise, for example, aim to spend six minutes on this. It can be tempting to blast through these sections, especially if you are worried about translations, but I do not recommend this. The marks are here for a reason; take your time, look for false friends and hints in the rest of the question, and write your answers methodically.

As with all exams, do not leave gaps! This will garner no marks, so it is always worth writing something.

That said, with the translations, try not to write nonsense. The test is not nasty enough to ask you to translate gobbledygook from one language to another. If something in the language doesn’t make sense, try to reanalyse it. What rational thing could it mean? This is a more sensible approach than hoping that something meaningless is the answer; after all, translation is all about transferring something meaningful.

If you do not know a word, that’s OK. Is there a roundabout way you can express the same idea? Go for it! Is there a fairly similar word that would be appropriate? Give it a try!

For idioms and proverbs, remember that the aim is to get the meaning across, rather than clinging to the original as if it were a life-raft. In one of my homemade mock Spanish tests, for instance, I ask applicants to translate “the tables have turned” into Spanish. But for people in Madrid, Mexico City, or Montevideo, no such idiom exists about whirling, revolving tables. Instead, transfer the meaning - I am far happier when a student simply writes “the situation is different” in Spanish.

Whilst there might happen to be an equivalent idiom in the target language, the examiners do not expect you to know it - you do not need to write “roasting two pieces of meat on one fire” in Polish. Simply state that two things can be achieved with little effort.

There is no need to be in thrall to the word order of any given language. Does the sentence sound better if you rearrange the noun and the verb? Then say it like that! Remember: producing natural, native-style language is the aim.

If you are taking two language tests, do not be tempted to favour one over the other. A student applying for French and English, say, will be devoting their full 30 minutes to French alone - and therefore so should you.

Are you applying for Languages at University/ Oxbridge?

Our Modern Foreign Languages Summer School offers an opportunity to delve into and explore both the cultural and linguistic aspects of the language(s) you choose. Students may choose which languages they will take (4 classes in each) of French, Spanish and German. Gain analytical & critical discussion skills in a stimulating and challenging environment.

Language Aptitude Test / Oriental Languages Aptitude Test (OLAT)

Note: the term used in this guide is LAT, though all information is applicable to the OLAT.

WHAT THE TEST LOOKS LIKE

I’ll be honest, I think this test is really fun. If you’re keen on learning a new tongue; this should be right up your street.

The LAT is essentially a language-based puzzle, based on a language invented especially for that test. You will be given a series of sentences in this language, with accompanying English translations. Your task in each section will be to translate sentences in the language into English, and from English into the language. This calls on three main skills: careful grammatical analysis, pattern recognition, and generalising from the data you are given.

The test is linear, by which I mean that question B will build on, and expect, knowledge gained from section A. Therefore it is always best practice to work through the sections in order. Do not be tempted to skip ahead when sitting a test of this kind, even if (and this is common) it feels like the clock is against you.

There are usually 3 or 4 sections to the test. 4 sections used to be most common, but in recent years more tests have appeared with only 3 sections (the trade-off is that you might have more to notice and track in each section!).

WHAT ARE THEY LIKELY TO ASK?

This is a difficult question to answer: there is no set syllabus, no target to aim for - hence it being an aptitude test, and not a knowledge test. However, the central task is to untangle grammar, and then to be able to deploy it.

Some of the features on display will be familiar to you from English, and are common to all the world’s languages. For example, there is generally a way to distinguish subjects from objects (English does this through word order, whereas Greek has a case system; either or both may be present in the LAT). There is also generally a split between nouns and verbs. The test expects you to recognise how the new language indicates these fundamental differences, and to replicate it.

Some of the features, however, will be unfamiliar to you if (as is likely) European languages are what you know best. Some languages in the world, for instance, place gender markers at the start of a word - whereas in Europe, placing them at the end is the norm. There is no way to be familiar with all the grammatical features that the world’s languages display - and, in fact, there is too much diversity for any one human to master anyway (but if you want to try, I recommend Linguistics as a subject!). Instead, what the test expects is for you to approach these new features with a flexible and open mind. The English translations are there to help you: the grammatical nuances present there will also be present in the language, in some way, and it is your job to spot them.

PREPARATION CHECKLIST

There are things that one can do to prepare for the language section of the MLAT without sitting a past paper, but I do not believe this is the case for the LAT. Instead, I recommend diving straight in and giving a test a try.

There is no particular order in which you need to sit these tests, though many students sit them from oldest to newest - and this is a decent strategy. Some tests are, in my opinion, harder than others - but this is just a personal opinion. It is not the case that tests are getting harder year-on-year; it is not a linear or chronological progression.

Some students “get” a test quicker than I did, for instance, and everyone’s ranking of tests from “easiest” to “hardest” tends to be different! Personally, I find the 2011 test (a language called Dobla) to be an easy starting point, but this will vary from person to person. So do not be daunted if a particular test takes a long time to “click”.

Have some different-coloured pens (or pencils, or highlighters) to hand. Personally, I find this indispensable - use one for nouns, one for verbs, one to mark word order, and so on. I also recommend practising on paper, and not on a screen. Do not trust your mind to retain all the new information the test throws as you - there is a lot! Outsource that job to the pen and paper.

STRATEGY

Before starting a test, read the introduction. After having sat one or two tests, it is tempting to jump straight in and “save time” by going directly to the data. But this is a false economy; the introduction sometimes contains valuable information. Some tests have word order which you will have to follow, for instance. Some do not. Since your task is to accumulate information throughout the test, don’t miss step one!

Look for commonalities. This sounds vague, and by necessity it has to be! We cannot predict the distinctions that the test might expect you to find - so again, on any given test, look at what is similar from line to line, and build a generalised rule.

That said, you can use the English to help you winkle out those commonalities. Are the English translations very fussy about the difference between lions and lionesses, for example? This probably means that you are expected to notice some way in which the language denotes grammatical gender - so try and find it. Do you have verbs that appear in both singular and plural forms in the English, or perhaps “we” and “they” forms? You will probably need to find an equivalent in the target language, and add them to your rules.

Sift out the stems, and the grammatical particles. Here’s what I mean:

A “stem” is the kernel of the word’s meaning. In the word “unfinished” in English, to illustrate, “finish” is the stem, because it gives us the central purpose of the word. A negative prefix “un-” and a past tense suffix “-ed” have been attached, and these are both examples of “grammatical particles”.

Note that the grammatical particles above are prefixes and suffixes, but they don’t have to be in the LAT. Imagine a language with the word “gosp” in it, meaning “he eats”. If you are told that the word “goosp” means “they eat”, or that “gösp” means “he ate”, this is also an example of a grammatical distinction made without adding prefixes or suffixes. English can do this too: I run, I ran, for example.

These are the sort of things that you should be aiming to track. Use those different coloured pens if you like - one for stems, one for particle rules.

In brief: account for every letter in a word - you should try to allocate it to either a stem, or a grammatical particle that gives you the grammatical nuances and purpose of the word itself.

Bear in mind that, above, I have been using the word “rules” above, rather than a word like “lists”. This is deliberate. This test is not just about listing the things that you find: it is also about understanding them, and then applying them. I asked you to look for commonalities, and to sift. This is so that you can make a generalisation about what the language does - an all-purpose rule you can make use of in a given circumstance. We have a word for this: it’s grammar. This is how to truly excel at the LAT: by filtering out the stems, by organising the grammar, and by applying it. Answers should not be just “found” in the data (the answers you need do not necessarily appear in the sample text), and nor will it ever need to be guessed. Instead, look for a process by which you can generate the right answer.

This, like the MLAT in general, is a skill rather than a talent. You will find the first LAT difficult. But I promise, the second will be less alien. So will the third - and so on. You will soon be familiar with the style in which the test operates.

If you run out of LATs in your preparation, you might like to look at the Linguistics section of the MLAT (present up until and including 2019) and the non-Latin, non-Greek portion of the Classics Aptitude Test. The format is not the same, but both tests contain two language puzzles based on languages that are likely unfamiliar to you. Not only are these, again, rather fun puzzles, but they will also expose you to more grammatical tricks that the world’s languages have up their sleeves.

A NOTE ON TIMING AND RULE-BUILDING

Whereas I think it is realistic to complete the whole language portion of the MLAT (e.g. the Portuguese section of the paper) to a high standard in the given 30 minutes, I do not believe this is the case for the LAT.

There is always a trade-off to be made between speed and accuracy. It is rare, practically unheard of, to finish a LAT flawlessly in the time limit. I will be open with you: when it comes to speed or accuracy, I do not know which (if either) is preferred by Oxford in the marking; this is not publicly-released information.

This, though, is another reason why I wish to emphasise the importance of rules, and not lists. This is a more efficient use of time than trying to make lists.

I especially advise against lists of stems, or lists of vocabulary. There is usually more than one person can track, and nor will you need to use all vocabulary when answering the questions. So do not waste time on this. Instead, try and look up vocabulary as and when you need it. This might feel time-consuming, and to an extent you’d be right - but it’s less time-consuming than making lists of unnecessary vocabulary.

Here is how I suggest dealing with the time limit:

For the first few practice tests (maybe the first three or so), I recommend not watching the clock at all. This is not a stress that you need as you become accustomed to the LAT.

From there, begin timing the 30 minutes. But for practice and for familiarity, I recommend finishing a mock test even after the 30 minutes have elapsed, even if you know this won’t be possible in the exam itself; the value you get from rule-building practice will be worth it.

So, what to do on exam day? I know it sounds cliché, but I recommend going as far as you can, but also as accurately as you can. In my opinion - and I should stress that this is just an opinion - aiming to finish the test is not the goal. I do not believe that Oxford is expecting a completed LAT. Instead, show your mastery of the rules, and press as far as you can go.

AFTER THE TEST

Put it from your mind. No, I mean it. Though it won’t feel like it, the MLAT is not a make-or-break part of the application process. It is one of several factors; your written work is another, your personal statement is another, and there are more.

It is also not worth comparing performance on test day to other practice tests you have sat. Some tests - the LAT especially - are simply more difficult than others, and it is not dependent on the year. If you found it hard, it’s likely that all students found it hard. Trust that you gave it your best shot, and shift your focus to the next (and final) portion of the application process: the interview.

This has been a long article - if you have made it to the end, thank you. I urge you to take these tests as what they really are: puzzles. The MLAT is a rare beast in the testing world, as it genuinely invites (and rewards) both creativity and open-minded thinking. Get accustomed to the structure, get practising, and (I promise, this is possible!) have fun while doing so.

How can U2 help prepare you for the MLAT/ OLAT/ LAT & wider applications?

U2 offer admissions test preparation either as part of our wider Oxbridge Mentoring programmes or as separate ad hoc tuition (book a free consultation to discuss options).

The Process:

1) We suggest an Oxbridge Modern Foreign Languages graduate as a mentor and send their full CV for review. Our tutors are deeply familiar with the admissions process to study Languages at Oxbridge, and we have tutors who specifically specialise in preparation for each specific admissions test.

2) We typically suggest beginning with a 1.5 hour informal assessment/ taster session, where the mentor will informally assess the student’s current performance level for test (and interview if desired). Following this, we issue a report with feedback, and structure a plan to best prepare. For the admissions test, this session will typically involve going through a past paper, identifying areas for practice and getting an idea of what to expect from the applicable admissions test.

3) Regular Admissions Test Sessions:

Students typically embark on regular admissions test sessions (most often weekly, though if preparing closer to the time, we can customise more intensive sessions/ test courses). Frequency of sessions can be decided between student and tutor after the first aptitude session. When the student and mentor run out of past papers, they will work through similar questions curated by the tutor. We offer MLAT/ LAT/ OLAT practice online or in-person in London.

Individual sessions from £70/h.